While fluorescence allows us to highlight subcellular structures, we still cannot resolve much of their detail. This is because the resolution of microscopy is limited by the wavelength of the imaging beam. For light microscopy, the wavelength of the photons limits the resolution to a few hundred nanometers (more powerful for higher-energy blue light and less for lower-energy red). This resolving power is on the order of the width of many bacterial and archaeal cells. There are some technical “super-resolution” tricks to more finely pinpoint fluorescent molecules, but the overall subcellular details of bacteria and archaea are beyond the resolution of light microscopy.

One way to get around the resolution barrier is to use an imaging beam of higher-energy/shorter-wavelength particles. The discovery in the early 1900s that electrons have wave-like properties, and the subsequent realization that they can be focused by a “lens” consisting of a toroidal magnetic field, led to the development of electron microscopy (EM) in the 1930s.

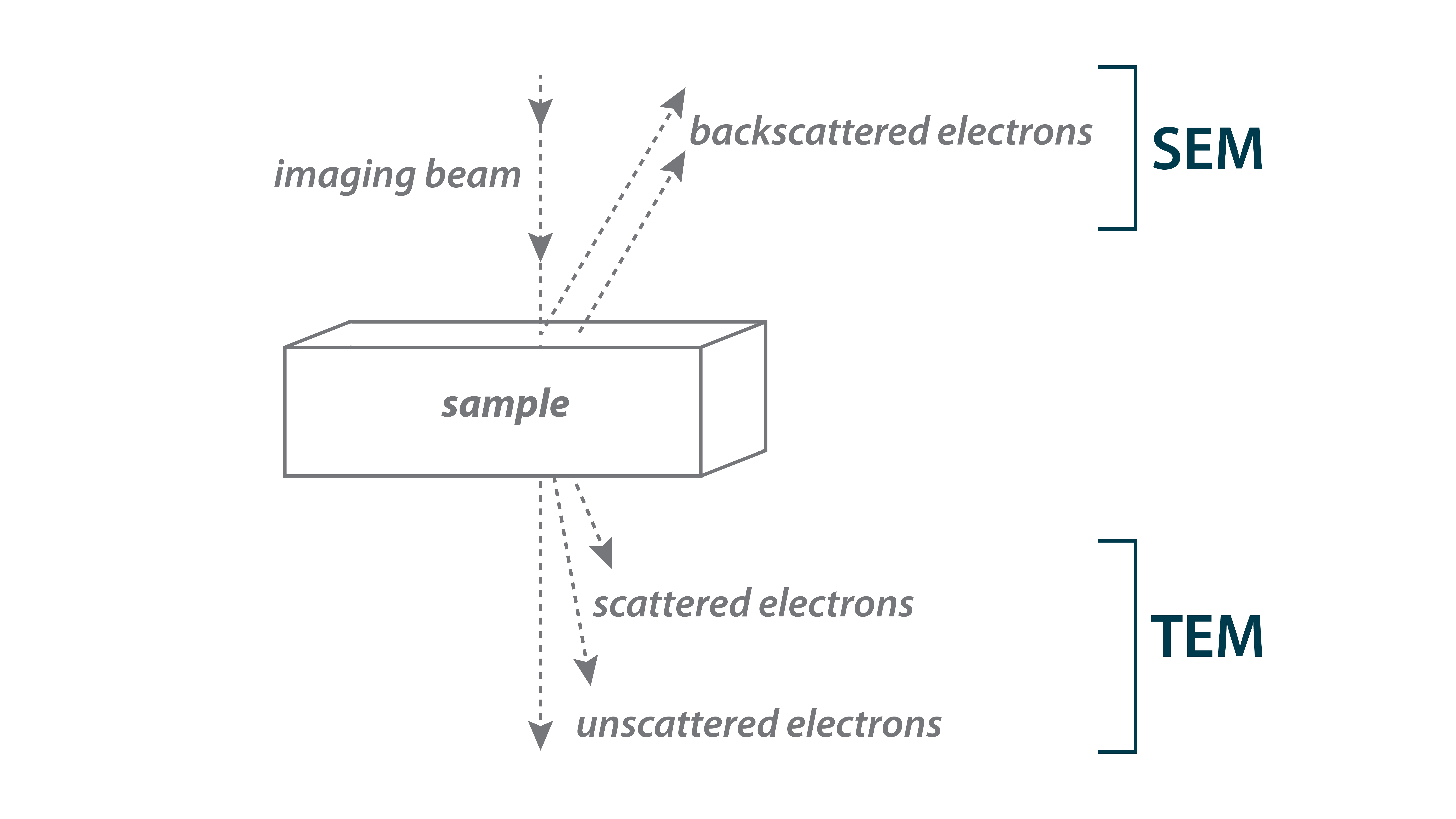

There are two main electron microscopy approaches (⇩). In Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), we detect electrons that are scattered backward from the sample, producing an image of the surface of the sample. The Shewanella oneidensis cells you see here were imaged by SEM. Note the magnified details of the cells’ shape and flagella compared to the light microscopy images you just saw.