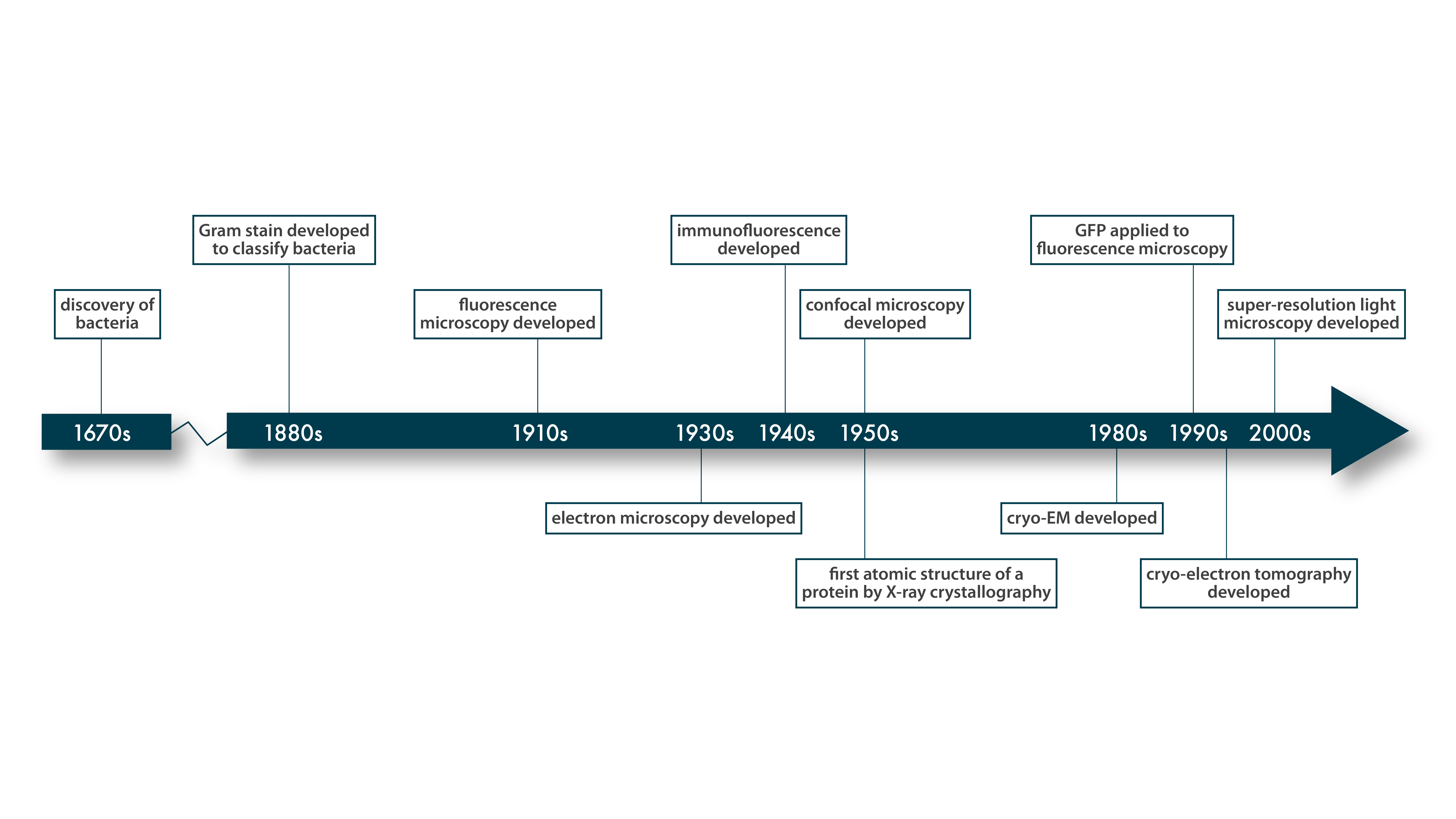

This chart gives a rough idea of when key techniques in structural biology were developed.

For smaller protein complexes and individual proteins or pieces of proteins, we can use a different technique, based on photons produced by electron interactions: X-rays. This technique, too, relies on a kind of averaging of many particles, in this case identical molecules that have been purified from the cell and crystallized. The wavelength of X-rays (~0.01 - 10 nm) is on the order of the distances between atoms in the crystal, which means that the atoms’ electrons scatter the X-rays into a diffraction pattern that can be used to deduce the precise arrangement of each atom in the crystal. Beginning in the 1950s, X-ray crystallography has been enormously successful in revealing the structure of biological macromolecules like proteins and, famously, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) polymers (⇩).

Not every protein can be induced to form large, well-ordered crystals, but many can, and as of 2020, X-ray crystallography had been used to solve nearly 150,000 structures, including the one you see here, which shows the interaction between the tail of the protein you saw on the last page, FliF, and the head of another protein, FliG, that helps form the other ring complex of the rotor [12]. This interaction locks the two rotor components together. PDB: 5WUJ

This chart gives a rough idea of when key techniques in structural biology were developed.