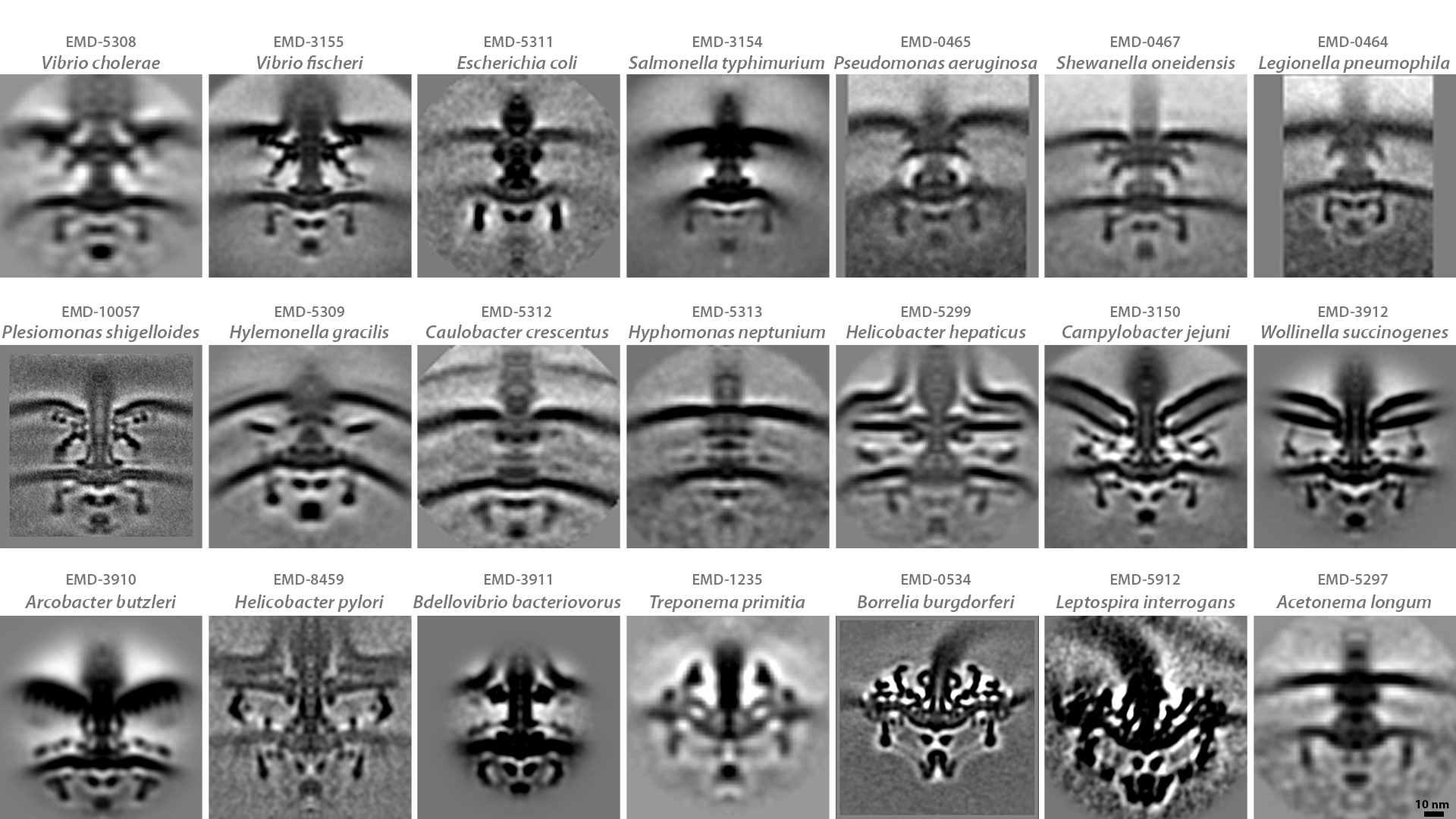

This is an average of the flagellar motors from more than one thousand Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus cells. Working upward from the base, the major parts of the rotor are the C-ring (for Cytoplasmic), the MS-ring (for Membrane and Supramembrane), the rod, the hook, and finally the filament. The hook and filament are at different angles in different images so they wash out in the average. The rotor is surrounded by non-rotating parts: the stator ring (which is dynamic, with various conformations that wash out when averaged, so we cannot resolve the stators as they cross the inner membrane and connect to the C-ring) and a series of bushings that allow rotation within the cell wall (the Periplasmic or P-ring) and outer membrane (Lipopolysaccharide or L-ring). Additional cytoplasmic components form the export apparatus, which is involved in assembly (discussed on the next page). The unlabeled components you see are specific to this and closely-related species (⇨).